Convex Optimization Note(3): Convex Optimization

1. Optimization Formulation

Eliminating Linear Equality Constraints

For a linear equation constraints \(Ax=b\), supposing the corresponding feasible set is \(S=\{x|Ax=b\}\). The constraint can be eliminated by substituting \(x\) with \(x_0+Fz\) where \(x_0\) is a particular solution of \(Ax=b\) and \(F\) is a basis of the null space of \(A\). Thus, we do not need constraints on variable \(z\).

Conditions: \(RF=ker\ A\), \(x_0\in S\)

\[x\in S \iff x-x_0\in ker\ A \iff x-x_0\in RF\iff x-x_0=Fz\]

Null space of matrix \(A\): \(ker\ A=\{x|Ax=0\}\)

Range of matrix \(F\): \(RF=\{Fx|x\in\mathbb{R}^n\}\)

2. Convex Optimization

Basic formulation of convex optimization problem:

\[ \begin{aligned} \min_{x\in\mathbb{R}^n}&f_0(x) \\s.t. &f_i(x)\leq0,\ i=1,...,m \\&a_i^Tx=b_i,\ i=1,...,p \end{aligned} \]

where:

\(f_0, f_1\dots f_m:\mathbb{R}^n\rightarrow\mathbb{R}\) is convex

\(h_i\) is affine

Optimality Conditions

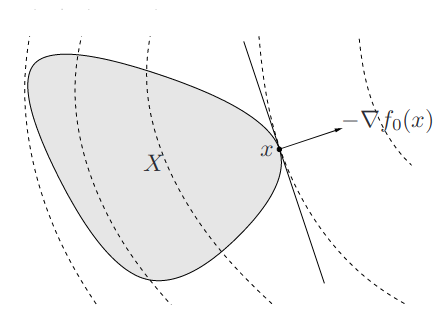

In convex optimization, a local minimum is also a global minimum. The optimal condition is: \[\nabla^Tf(x)(y-x)\geq0,\ \forall y \in\text{feasible set}\] Geometrically, it means that \(-\nabla^Tf(x)\) is a supporting hyperplane of the feabile set at \(x\). (if \(\nabla f(x) \neq 0\))

Unconstrained problem: \(\nabla f(x)=0\)

Problem with only equality constraints: \[ \begin{aligned} \min_{x}\quad&f(x) \\s.t. \quad &Ax=b \end{aligned} \] \(y-x\in \mathcal{N}(A)\) since they are both in the feasible set. Thus, \(\nabla f(x) \perp \mathcal{N}(A)\) > If a linear function is non-negative on a subspace, then it must be zero on this subspace.

Non-negative orthant \[ \begin{aligned} \min_{x}\quad&f(x) \\s.t. \quad &x\succeq 0 \end{aligned} \] After deduction, we can get \(x_i(\nabla f(x))_i= 0\), which is a complementarity condition. This can also be achieved by KKT condition.

Quasi-convex Optimization

Only the cost function is quasi-convex compared to convex optimization. For quasi-convex constraints, we can always find a convex constraints that is equivalent to the original one(same 0-level subset).

\[\nabla^Tf(x)(y-x)>0\quad \forall y\in \mathcal{X}/x \implies x \text{ is global optimal}\]

Only sufficient

gradient non-zero

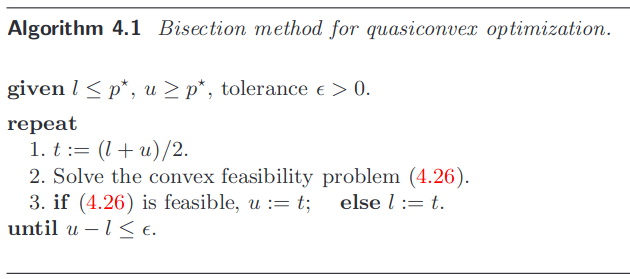

Bisection Method: From quasi-convex to convex optimization

For a quasi-convex problem, we can use bisection method to find the

optimal solution. The idea is to use a convex function family \(\phi_t(x)\) to approximate the original

function \(f(x)\): \[f(x)\leq t \iff \phi_t(x)\leq 0\] Then try

to approximate the optimal solution \(p^*\):

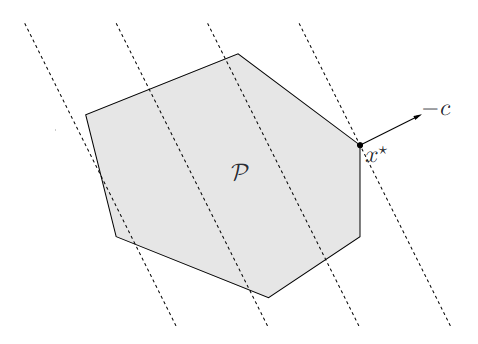

Linear Optimization

All the constraints and objective are affine.

\[ \begin{aligned} \min\quad & c^Tx+d\\ s.t.\quad & Gx\leq h\\ & Ax=b \end{aligned} \]

Geometric interpretation of linear optimization:

Linear-fractional Programming

The objective is a ratio of affine functions: \[ f_0(x)=\frac{c^Tx+d}{e^Tx+f} \] This is a quasi-convex optimization.

Quadratic Optimization

The objective is a quadratic function and the constraints are affine. \[ \begin{aligned} \min\quad & \frac{1}{2}x^TPx+q^Tx+r\\ s.t.\quad & Gx\leq h\\ & Ax=b \end{aligned} \]

If the inequality constraints are quadratic(convex), the problem is

called quadratically constrained quadratic

programming(QCQP). If the constraint can be written as \(||Ax+b||_2\leq c^Tx+d\), it is called

second-order cone programming(SOCP). Their relationship

can be expressed as following:

Example of a robust linear programming problem: \[ \begin{aligned} \min\quad & c^Tx\\ s.t.\quad & a_i^Tx\leq b_i,\ i=1,...,m \end{aligned} \] The \(a_i\) lie in a elipsoid: \[ \begin{aligned} a_i\in\mathcal{E}_i=\{a_c+P_iu\quad|\quad ||u||_2\leq 1\} \end{aligned} \] The constraint can be reduced to: \[ \begin{aligned} a_c^Tx+||P_i^Tx||_2\leq b_i \end{aligned} \] Which is a SOCP. With similar method, we can transfer a random linear constrained problem into an SOCP problem: \[\textbf{Prob}(a_i^Tx\leq b_i)\geq \Phi\]

Geometric Programming

Forms that are not convex originally but can be transferred into a convex function by its Monomials and Posynomials formed constraints.

Monomials: \(f(x)=cx_1^{a_1}x_2^{a_2}\dots x_i^{a_i}\)

Posynomials: Linear combinations of monomials

Convex Optimization in the form of Generalized Inequality

The standard form of convex optimization can also be expressed through generalized inequality. In the following chapters, we will see this can also be solved as easily as ordinary convex optimization problems. \[ \begin{array}{ll} \operatorname{minimize} & f_0(x) \\ \text { subject to } & f_i(x) \preceq_{ \text { K }_i} 0, \quad i=1, \ldots, m \\ & A x=b, \end{array} \]

Conic Form Problems

The conic form problem is a special case of the generalized inequality problem. It has a linear objective and one affine inequality constraint: \[ \begin{array}{ll} \operatorname{minimize} & c^Tx \\ \text { subject to } & Ax+b \preceq_{ \text { K }} 0 \end{array} \] If \(K\) is the non-negative orthant, the problem is a linear programming problem.

Semi-definite Programming

The semi-definite programming is a special case of the conic form problem when \(K \in S_+^k\) is the cone of positive semi-definite matrices. \[ \begin{array}{ll} \operatorname{minimize} & c^T x \\ \text { subject to } & x_1 F_1+\cdots+x_n F_n+G \preceq 0 \\ & A x=b, \end{array} \]

The inequality constraint is a linear matrix inequality(LMI) if \(F_i,G\) are diagonal.

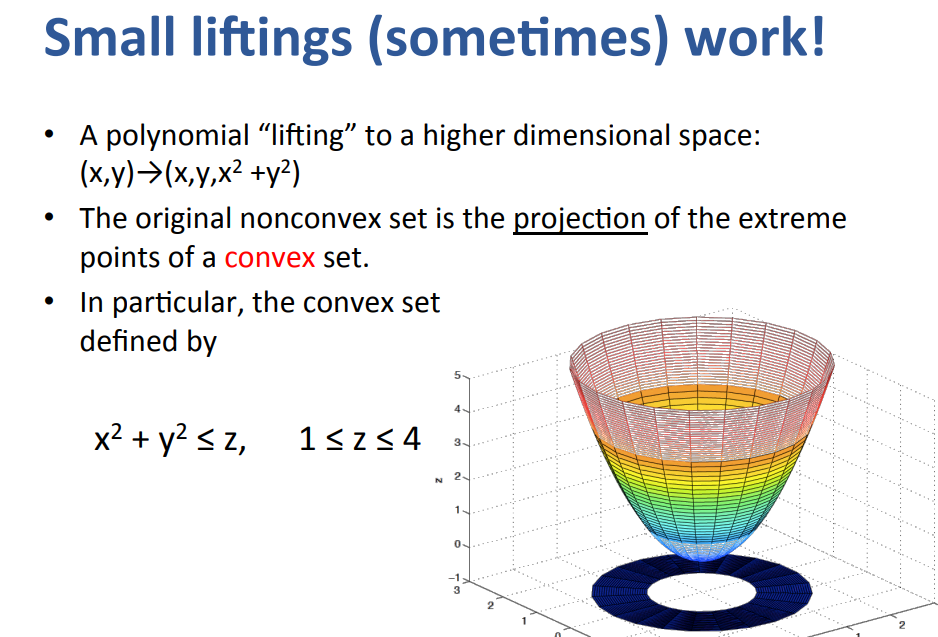

Here is an example of converting a non-convex problem into a semi-definite programming(thus convex) problem through "lifting". It is just a simple example to leave some impression of SDP. We will see more examples in the following chapters. The figure comes from here.